The following is an essay previously submitted for assessment purposes at the University of Queensland.

According to an issue brief by the Centre For Policy Development (2011), Australia has one of the highest levels of concentrated media ownership in the Western world, and this has greatly impacted what is defined as the ‘public interest’. The debate on what constitutes as the ‘public interest’ often involves a question of the role that the press/media plays in society.

The Social Responsibility Theory (first mentioned in the Commission on Freedom of the Press in 1947) is a normative theory of the press, which suggests that the press has a moral obligation to serve the needs and interests of the public. The press has to be truthful, fair and comprehensive in its reporting, aiding the public in evaluating information sources and forming informed opinions, thus serving the ‘public interest’.

However, the media in today’s information landscape is unequivocally commercial, because of private capitalist control over the news media, combined with advertising providing the majority of revenue (McChesney, 2012). Because of such corporate (and even governmental and private) interests, the media in today’s society is often guided by principles that may contradict the independent political purpose of the Fourth Estate rhetoric (Schultz, 1998), thus impacting what is traditionally meant by the ‘public interest’.

The aim of this essay is to outline and discuss the large extent to which a concentration of media ownership has impacted the public interest. In my paper, I will define the key terms that are central to the issue, as well as provide my argument and reasons as to why I believe that the Internet has propagated such a phenomenon. For the purposes of argument, the scope of this essay is centred on a concentration of media ownership in the commercial model of the media, and examples mentioned are generally contextualized in Australia (unless stated otherwise).

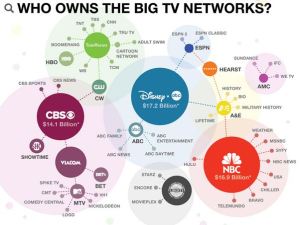

It is no surprise that the media industry today is dominated by an oligopoly of large media conglomerates, such as The Walt Disney Company, News Corp, Time Warner and the CBS Corporation, owning many of the major television networks, newspapers and other mass media outlets worldwide. As seen in the visual below (Fig. 1), The Walt Disney Company, CBS Corporation and NBC control the majority of the major television networks in the United States, with a combined net worth of over $48.2 billion.

Figure 1 – Top media conglomerates and the TV networks that they own in the US. Source: Skewsme.com

The concentration of media ownership is often seen as a problem of contemporary media and society. (Ainger, 2001) Here, a concentration of media ownership (also know as media consolidation) is essentially defined as a process whereby progressively fewer individuals or organizations have increased control over the mass media, as a result of large media companies or wealthy individuals buying over television networks and newspapers, usually for profit and market share. That being said, one criticism of such media consolidation raises the issue of the media’s role in society, and whether a monopolistic or oligopolistic control of a media market can adequately serve the public interest above profit interests.

A vague term central to the discussion – and often used as an argument for the concentration of media ownership – is the idea of the ‘public interest’. What fundamentally constitutes as the public interest? There is no clear definition. However, there are two main interpretations for such a concept of a public interest with regard to the media; first, the idea that the individual should be given the autonomy to dictate his own consumption habits, thus allowing the public to decide what they want, or second, that the media owners should determine what is best for the public interest, even though it may not be what the public demands.

Croteau & Hoynes (2001) identify two different models of the mass media – a market model and a public sphere (or state) model – which affect the way the public interest is seen. (Shmykova, 2007) One theory of the media that affirms the public sphere model is the Public Interest (Pigouvian) Theory, in which a state ownership of the media is desirable because, amongst other reasons, it allows the media to expose the public to an impartial, more comprehensive and more accurate information that it could with private ownership. (Begoyan, 2009) In this instance, information is a public good (Begoyan, 2009), and the public interest is served through the presence of “diverse, substantive and innovative content, even if not always popular” (Croteau & Hoynes, 2001, Shmykova, 2007).

On the other hand, a commercial or market model of media ownership holds that the interests of the public is served based on demand and supply forces, essentially defining public interest as what the public is interested in and what it demands. The primary orientation of such a commercial model is to maximize profit (seen as a measure of success) (Shmykova, 2007), and the popularity of content is valued over its diversity and information. Quite often, the emphasis on sensationalism of stories is evident in what is reported in the media, riding on entertainment value to push content.

There is no doubt that the concentration of media ownership can severely impact the public interest. Some opponents of media consolidation argue that a “monolithically owned media will create content that is one-dimensional, and therefore lead to a less-informed public” (Kenix, n.d.). This is because the owners of media organizations have the ability and capacity to determine what information, such as ideas, facts and versions of them, reach the public (Hutchins et al., 2000). It also can result in the marginalization of interests of the poor and working class because of the reduced diversity of opinions in the media, as well as grant corporations and media owners tremendous political power (McChesney, 2012) to influence the political landscape to best suit their business interests.

In the case of Australia, the high concentration of media ownership has “lead to concerns about the implications of having so much potential to influence public opinion and elected governments in so few hands.” (Centre For Policy Development, 2011) Given that two large media conglomerates –News Limited and Fairfax – dominate the Australian media landscape, this essentially means that the two companies (and their respective heads) would be afforded the power to set the ‘narrative agenda’ for the news that reaches Australians. This is affirmed by the ‘Class-Dominant Theory’, which argues that media often reflects and portrays the views of a minority elite which controls the news media, affording them the ability to manipulate what people see and hear on a daily basis. Whilst the media may not be able to dictate what the public thinks and believes, they most certainly can tell the public what to think about.

A recent example would be News Corporation owner Rupert Murdoch’s involvement in the 2013 Australian Federal Election, highlighting the controversy of media moguls possessing tremendous political influence. News Corporation is the largest newspaper publisher in Australia with a 59% market share (Taylor, 2013), owning many widely circulated newspapers such as The Courier-Mail, The Daily Telegraph and The Herald Sun.

Figure 2 – The Daily Telegraph front page, urging Australian voters to vote against Kevin Rudd and the ALP. Source: Business Insider

It is evident that Murdoch’s position as the head of a large media organization affords him the power to dictate what is reported (and what isn’t reported) in the media outlets that he owns. As seen above (Fig. 2), Murdoch makes his political inclinations clearly known, using a widely circulated newspaper (The Daily Telegraph) to urge Australians to vote against Kevin Rudd. It is evident that media moguls such as Rupert Murdoch have tremendous political influence, and they are often able to wield such power to delay or veto policies that would pose a threat to their influence, such as media ownership regulations and policies.

Figure 3 – Another front page of The Daily Telegraph, comparing Kevin Rudd to a Nazi officer. Source: Business Insider

Idealistically, the media is supposed to be fair, comprehensive and impartial in it’s reporting, thereby serving the public interest by aiding people to make informed decisions on issues based on a fair presentation of facts. “Content in the media should be independent from corporate and governmental interests.” (Shmykova, 2007) However, as seen in the above example of Rupert Murdoch, a concentration of media ownership can result in an affordance of content manipulation and distortion of opinions, which severely impacts the idea of the public interest (Fig. 3). As The Independent Australia (2011) states: “The Australian people have less voices to use upon which to make their decisions than almost any other place in the world. And Rupert Murdoch is happy to wield his overwhelming power.”

It can be argued that the rise of the Internet has somewhat placated the ill effects of a concentration of media ownership, by offering a diverse range of sources of news that media consolidation seemingly does not. Given the relatively large barriers to entry in the mass media industry (i.e. cost of printing newspapers and operating television networks), the Internet has afforded smaller media organizations the opportunity to broadcast information to the public on a large scale, without bearing huge costs. Crikey states in its mission that “Crikey is a showcase of information that might otherwise remain suppressed…information they believe is in the public interest” and that “Crikey is independent and not part of a media empire.” (Crikey, 2000) A common rhetoric of independent media outlets is that the news they provide are free from commercial and governmental interests, and that they are there ‘for the people’.

However, even though there are several independent news outlets available to the public, their presence has done little to hinder the impact of a concentrated media empire. While the Internet does provide people with a plethora of alternative news and information sources, people still typically seek their news from already-existing media ecosystems (Centre For Policy Development, 2011), which are probably under the concentrated media empire. Some are also sceptical about the reliability and accuracy of independent news outlets, preferring to trust in larger media outlets that have more financial power, which generally translates into better professional norms and editorial accountability.

In my opinion, the proliferation of digital communication and technology – or the rise of the Internet in general – has somewhat propagated such a situation. According to the Pew Internet & American Life Project (2010), news in today’s media environment is becoming more portable, personalized, and more importantly, participatory, partially because of more media organizations encouraging “reciprocal communication between users and media” (Ha & James, 1998). The relatively easy access to mobile devices and the Internet has made online news consumption available to almost anyone, and the media empire is looking to take advantage, through simplifying the news consumption experience through innovative means such as dedicated mobile phone applications (apps). Apps such as these allow the public to easily access the news with a few simple actions on their mobile devices, without the fuss of having to navigate through webpages on a computer or the newspaper. This would undoubtedly appeal to the public, thus keeping them contented with the user experience as well as the news they are receiving, and ensuring that they remain connected to that particular media outlet.

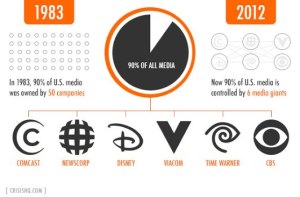

In conclusion, the concentration of ownership in today’s mass media outlets has had a profound and severe impact on the idea of the public interest in today’s societies. As more and more media outlets are being subsumed under the giant media conglomerate umbrella (Fig. 5), homogeneity of content will undoubtedly occur in the relationship between the mass media and the public interest – a problem that has to be addressed eventually.

Figure 5 – Comparison of the media landscape between 1983 and 2012. Source: Clearancebinreview.com

Media plurality (i.e. multiple media outlets) is essential in “providing the opportunity for diverse voices to be heard and ideas to be circulated.” (Begoyan, 2009) All types of diversity are important to serve the public interest (Shmykova, 2007), as it will ensure that the interests of different audiences are addressed. In my opinion, the only way forward is to ensure a structure of regulation in the media industry, so as to ensure that there is a range of diverse content available for the public. This would also involve analysing the wider consequences of the high levels of concentrated media ownership, thus allowing feasible evidence to back appropriate policies of ownership regulation. Until that is done, there is little to stop the onward march of the likes of News Corporation and Fairfax.

References:

Ainger, K. (2001). Empires of the Senseless. New Internationalist Magazine. Retrieved from http://newint.org/features/2001/04/01/keynote/

Begoyan, A. (2009). State versus private ownership: A look at the implications for local media freedom. Retrieved from http://www.article19.org/data/files/pdfs/publications/poland-article-19-report-on-media-ownership.pdf

Centre For Policy Development. (2011). Issue Brief: Media Ownership and Regulation in Australia. Retrieved from http://cpd.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Centre_for_Policy_Development_Issue_Brief.pdf

Corporate controlled U.S. Media [Image] (2013). Retrieved from http://skewsme.com/tinfoilhat/chapter/information-control/#axzz2fPSpl0Dj

Crikey. (2000). About Crikey. Retrieved from http://www.crikey.com.au/about/

Croteau, D. & Hoynes, W. (2001). The Business of Media: Corporate Media and the Public Interest. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Ha, L. & James, E. L. (1998). Interactivity re-examined: A baseline analysis of early business Web sites. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 42(4), 456 – 474.

Hutchins, R. M., Chafee, Z., Clark, J. M., Dickinson, J., Hocking, W. E., Lasswell, H. D., MacLeish, A., Merriam, C. E., Niebuhr, R., Redfield, R., Ruml, B., Schlesinger, A. M., & Shuster, G. N. (2000). Freedom for what?. Nieman Reports, 53/54, Issue 4(1), 7 – 11. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/docview/216747254/fulltextPDF?accountid=14723

Kenix, L. J. (n.d.). Alternative and Mainstream Media: The Converging Spectrum. Retrieved from http://www.bloomsburyacademic.com/view/AlternativeMainstreamMedia_9781849665421/chapter-ba-9781849665421-chapter-007.xml?print

McChesney, R. W. (2012). Farewell to Journalism?. Journalism Practice, 6:5-6, 614 – 626. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2012.683273

Media ownership model graphic [Image] (2013). Retrieved from http://clearancebinreview.com/2013/02/01/dr-geek-google-to-play-hollywoods-game/media-ownership/

Pew Internet & American Life Project. (2010). Understanding the Participatory News Consumer. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Online-News.aspx

Schultz, J. (1998). Reviving the Fourth Estate: Democracy, Accountability and the Media [Cambridge Books Online]. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511597138

Shmykova, E. (2007). Effects of Mass Media Ownership on Serving Public Interest. Retrieved from http://web.mit.edu/comm-forum/mit5/papers/Ekaterina_Shmykova.pdf

Taylor, A. (2013, September 8). Rupert Murdoch Got What He Wanted In the Australian Election. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com.au/rupert-murdoch-got-what-he-aimed-for-with-the-australian-election-2013-9

The Daily Telegraph Front Page [Image] (2013). Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com.au/rupert-murdoch-got-what-he-aimed-for-with-the-australian-election-2013-9

The Independent Australia. (2011). Concentrated media ownership: a crisis for democracy [Web log message]. Retrieved from http://www.independentaustralia.net/2011/philosophy/democracy/concentrated-media-ownership-a-crisis-for-democracy/